Most people seem to remember the low, mournful whistle. Not me. It's all about the smell for me. You see, the railroad works its way into your heart through your nose. It's the aroma of the coal smoke. It's the smell of grease warmed on hot cast-iron skillet. It's the aroma of wood ties baking in the hot sun. And all around, the fresh air bringing the smell of the woods or the factories, depending on where you were. Well, that's how it was back then, anyway.

At first, I thought the caboose smelled like my father. Turns out, my father smelled like that old caboose. I learned that on my first day working for the C&O.

It was the early 40's, and most kids a little older than me were off paying a certain Mr. Adolf Hitler a visit over in Europe . I'd join them in the South Pacific in a year's time, but I was home then, about to start my first real job. My father was a conductor, and he put in a good word for me down at the office. Probably, they would have passed on me until I was a little older, but "beggars can't be choosers," he explained.

So I rode my bike down to the freight yard in the freezing cold, about as nervous as I'd ever been. That day, I would become the newest--and youngest--brakeman on the C&O. Worse yet, my father would be my boss. And I couldn't let him down.

A freight yard is overwhelming to a newbie. Seemed like there were 100 parallel tracks were connected by a thousand switches, and the order of it all was just chaos to me.

Walking past the tower, I could see maybe a half dozen tank cars on one track, at least a dozen coal hoppers on the next track, and a bunch of freight cars that stretched as far as I could see on the track after that. Behind me, the bell on a creeping locomotive clanged, warning lost souls like me to keep out of its way. My ears burned in the cold.

"Tommy!" called the yardmaster. I looked up at him in the tower.

"Good morning, Mr, Johnston

"Better get yourself into that cabin car, or your old man's gonna tan your hide!" he hollered with a smile. "Track 5, Track 5! Oh, and see me to sign your papers when you get back--no time now! Welcome aboard, son!"

I waved and trotted along the freight cars standing coupled on track five. The red caboose was in sight, maybe twenty cars down. My father waved from the front platform.

At the caboose, my father handed me a pair of large leather gloves and checked his pocket watch as we went inside. There was that wonderful smell inside--grease and solvent and coffee and then just coffee as the pot came to a boil on the stove.

"I don't need to tell you that we keep a tight schedule," my father chided with a wink. "It's your first day, so I'll let it slide."

He stepped out onto the platform again, leaning off the side and signaling the locomotive with his hand. "We got Joe and Sam up front, so this will be an easy run." Joe and Sam were the engineer and fireman, an experienced crew, and more of my father's buddies. Joe answered my father with two whoops from the whistle.

"Brace yourself now," my father warned me as he handed me a cup of coffee, "Joe means business." As the locomotive moved forward, gaining speed, the slack went out between the cars, jarring each one until the jolt caused me to spill half my cup. My father skillfully took a swig at the right moment, and he didn't spill a drop.

"Well, good thing this isn't your mother's parlor." He winked again. "But let's keep this place clean." He tossed me a dirty towel, and I wiped the floor.

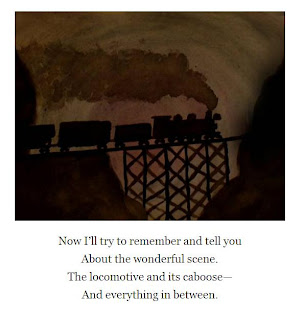

Now that we were underway, my father got down to work. He organized his paperwork--freight waybills, crew time sheets, train orders, explaining each document to me. Sure, I was a brakeman, but he was training me to be a conductor one day. And as the train entered a curve, he just about lifted me off the bench I was sitting on and dragged me over to the window for a spectacular view of the train. Sam waved at us from the locomotive's cab. We were now approaching our first stop.

"OK, here we go," my father said, buttoning his jacket and putting his work gloves back on. "Watch carefully. This is big equipment, and we need to make sure that we're safe. And this is a get-it-right-the-first-time kinda job."

He went to the platform and signaled to Joe to stop the train. We walked back a ways and dropped a signal to let approaching trains know that we were blocking the line, and then we walked up about 25 cars.

"We cut in here," my father explained, slamming the coupler open. He signaled to Joe, who answered back with two whistle blasts and pulled forward, breaking the consist in two. Once they passed a switch, they stopped the train.

My father demonstrated how to operate the lever and rotate the switch, preparing for the locomotive to back onto the siding to collect more cars. Then we walked down the siding where we were to collect three empty boxcars. My father stopped dead in his tracks when we were just about up to the first car. He flung one of his big arms out to block me, and I stopped in my tracks, looking over at him. I could tell he was concerned.

"We got company, I'd say," he whispered. I heard a loud cough echo from inside the boxcar. And then an unhealthy hacking cough, followed by a moan. "Hang back here, son. You never know with these guys..."

Now, I always knew that folks hopped aboard freight trains to catch a free ride. The stock market crashed over ten years earlier, and men took to the rails in droves, riding around until they found work. Or maybe just riding around because they had no other life to get back to. Problem was, there was always lots of booze, and where there's booze, there's trouble. When I was little, my father was roughed up by a few guys when he kicked them off the train. I was old enough to remember.

My father walked ahead of me. "All right!" he bellowed. "Out of the car! This is the end of the line for you." Everything was absolutely silent for a few long seconds until another raspy cough rang out.

The boxcar door slid open another foot or so, and an old man hopped down from the car. He wore a dirty jacket and carried a filthy bag. His right pant leg was torn at the knee, and his stubbly beard was mostly white. He was hunched forward a bit; he rubbed his crooked back after jumping down. Now he looked at us with a blank, defeated stare. He coughed again, and I could see his breath in the cold.

"Well, we can't have this," my father said. The old man looked down. "Where you headed, old timer?"

"Back to the city," the old man said, his eyes still fixed on the roadbed. He was waiting for my father to tell him to get off the railroad's property. That was the rule; in fact, he could be arrested for trespassing. And some railroad bulls would be more than happy to remove him toss him over a fence, just to get the idea across.

"The city, huh?" My father sighed. "Well, not in a boxcar. We can't have that. I won't tolerate it." He turns to me and winks. "No, I won't tolerate it for a moment. So you'll ride in the cabin car with us."

When I heard this, I was furious. Now, I'm not sure why, but it was as if I snapped. Was he serious? Didn't he know this was against regulations? Why would my father risk getting himself into trouble--and me--for some old stowaway? I didn’t want the superintendet coming down on him for this lapse of judgement.

"Father, you can't let him on the train!" I blurted. "Don't be wreckless! Even I know that'll cost us our jobs!" My ears were stinging again, and my hands were starting to ache. But my cheeks were warm with anger.

"I've got a lot to teach you still, don't I?" my father gently scolded, shaking his head. "We will be just fine," he assured me. I stood staring at the old man, and he looked at me, desperate and cold. "Well, both of you, come on," barked my father. "We have a schedule to keep and we're losing time. I am the conductor here. This is my train. And I won't be late."

We walked back to the mainline, where my father signaled Joe again with his hand. As Joe started to back down the siding, my father sent me to the back of the train to collect the signal. And to calm down. By the time I was back to the caboose, the locomotive had pulled the three empties off the siding, my father had thrown the switch, and Joe was slamming the train back together.

Without talking, I climbed the steps to the caboose with my father and his new passenger. The cabin was very warm. Again, my father signaled Joe, and off we went with a series of slams. Bang, bang, bang, as the slack was let out.

My father poured coffee into our tin mugs and got a third down from a shelf. He blew the dust out of it, then poured a cup for our passenger. Shortly, we made another stop to cut in two gondolas. The old man waited inside while we worked. Once we started out again, there was time to talk.

"We got another 12 cars to collect and 18 cars to drop off before we get back to the yard in the city," my father told us. "This is an easy trip with Joe and Sam up front." The old man nodded in polite agreement, but it didn't feel easy to me. "Say, what brings you to the city?"

"Going home," said the old man. "It's been over ten years since I been back." He coughed again.

"Ten years? That's a long time to be away."

"Well, I didn't plan on coming back."

"No?"

"No, I was looking to work in the South where the weather isn't so bad as this," the old man explained.

"I can imagine a little sunshine would do the body a world of good," agreed my father.

"Yes, that's right," the old man smiled. He rubbed his back for a moment. "It's harder to work outside at my age, but I was going to get by."

"So back to the city in the winter?"

The old man teared up a little. "I received word that my brother is taken ill, very ill," he choked out. "That was two weeks ago yesterday, and I hope he's still with us."

I felt burning ashamed. I was so selfish to try to throw this old man out into the cold. I fought back the tears that came from shame and from hearing this story.

Just then, Joe's whistle warned us of the next stop. And then the stop after that and after that. We got about two miles from the yard when my father reached for his wallet.

"Here's six dollars," he said, placing it in the old man's hands. "It's all I have, but it should be about enough for bus fare and dinner. When we stop the train the throw the switch at the yard, I'm going to ask you to get off and walk down the embankment. When you reach the street, make a right and keep going until you get to a diner. You can eat there and catch the bus around the corner."

I pulled two quarters from my pocket and gave them to the man, too. "I hope your brother is OK," I told him.

As Joe slowed the train, the old man thanked us and then hopped down from the last step on the platform. Despite the crooked back, the old man exited so gracefully that I could tell he had done it a thousand times before.

I stepped onto the back platform and waved as we continued forward through the switch into the yard. The old man waved back and then turned to press through the dry weeds.

I was so proud of my father that cold night. I can't hear a horn or a whistle or the clanging bell at a grade crossing without thinking of my father's kindness. Or the smell of coffee in that caboose.