Be sure to check out "The Reaping Sowing Rabbit" on Kindle.

My collection of story ideas, poems, and fragments. Best enjoyed with a cup of coffee.

Saturday, December 7, 2013

Saturday, September 7, 2013

Guess Who Has an Amazon Author Page?

Mr. Otel introduces his shiny new Amazon Author Page. Click here to visit: amazon.com/author/williamotel.

Not totally sure what good it is, but why not, right?

Not totally sure what good it is, but why not, right?

Wednesday, August 28, 2013

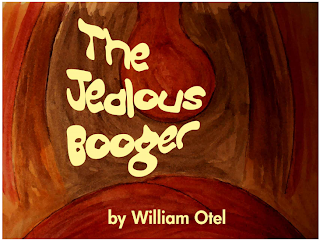

"The Jealous Booger" is now available on Kindle!

Here's the problem: Booger is jealous of Spit's bubbles. It's gross but true! Maybe you have a "jealous booger" in your family? Well, here's a simple, quirky story that children are sure to connect with. Kids will learn that everyone is special and see what comes of a selfless act of kindness. Great for a Sunday School lesson! Written and illustrated by William Otel, author of "I Dreamed a Train."

http://www.amazon.com/The-Jealous-Booger-ebook/dp/B00EBI5QQK

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Flash Fiction: The "Hit and Run" (work in progress)

Prepared by Sgt. James Griffin, responding officer

Chester County Sheriff Department

Preliminary report

Received call from dispatch at 2340 hours. A passing motorist

reported that a middle-aged male, Caucasian, 25-35 years old, wearing a white

T-shirt, was observed on the shoulder of Main and South. I made a U-turn

and headed south on South Avenue .

Received another call from dispatch at 2345 hours. A second caller

indicated that he struck a pedestrian with his silver Honda Accord. I radioed

dispatch and responded to the area of Main Street and South Avenue . The pavement was wet under a

slight drizzle. It was otherwise warm and humid.

Upon arriving on the scene, I witnessed a male matching the

description provided by the first motorist stomping through the knee-high weeds

in the ditch along the side of the road. He was approximately 30 yards behind a

burgundy Honda.

The man was visibly shaken. He repeatedly cried: “What have

I done!”

I demanded to see where the impact occurred, assuming that

the victim would not be far from that spot.

Scanning the area on both sides of the street, I was unable

to find any blood, shoes, etc. that would indicate that the collision occurred

at that spot. The man had stopped searching, but still muttered, “What have I

done?”

Finally, I detected an irregular pattern on the shoulder, as if something were dragged. My stomach sank as I looked down the road at the

back of the Accord, tail lights still on.

I whirled around to look at the man, who was startled by my

stare. “Did you drag someone?” I shouted at him, shining my flashlight in his

face.

“No, no, no, no!” he cried, holding and shaking his head as snot flowed from his nose.

“Please, no!”

I started running for the front of the car, my heart

pounding in my throat. “You stay right where you are!” I ordered the man.

I reached the front of the car, dropping to my knees to look

up the passenger side wheel well. Nothing. No one. The headlights were intact,

and the windshield had no cracks. Further investigation revealed that the marks

in the gravel were likely the lengthy skid mark.

“Hey, buddy,” I called. “Step up here to the squad car. Right

up here! Hands on the trunk.” The man complied, placing his raw, chapped hands

on the trunk. He sniffled and wiped his nose on his shoulder.

“Driver’s license and registration,” I demanded. An

ambulance pulled up behind us. The man reached around into his back pocket to

produce the documentation. Thomas Michael Halton, born November 28, 1987.

“Mr. Halton, can you tell me how fast your vehicle was going

when this incident occurred?” I asked, pulling my notepad out.

“I don’t know,” he said, calmer now. “Maybe 45, 50 miles per

hour.”

“At that speed, I would have expected to see some pretty

serious damage to your car,” I explained, half wondering out loud. The man looked

confused. “I see no evidence of impact,” I continued. “Did the victim run off

when you hit him—or was it a her?”

“No,” the man said. “I don’t think so.” He sighed.

“What did the victim look like? Male or female?” I asked.

He looked up out of the corner of his eyes, as if visualizing

the scene. “I don’t know,” he said. Suddenly, a wide smile. “Oh, thank God! I

don’t know! I don't know!” He beamed.

I searched his person and his automobile, with his permission, and found no contraband. Suspect was released with a warning to go directly home.

Friday, May 10, 2013

Story Excerpt: Sam Gets a Cat (and Various Barbeque Recipes)

A few months ago, I thought it would be a good idea to get a cat. I imagined snacking, watching TV, and napping with my new friend. Perhaps it could learn to use the toilet. Cats are very smart, you know.

Plus, in event of famine, cats are said to be tender and succulent.

Before long, Jean spotted a cat adoption at a pet store, and I quickly turned into the parking lot.

Inside the shop, five cats were stacked in cages. But only one special kitten reached through the bars.

“Jean, this is the perfect cat for us,” I declared. “I guess,” she replied. She was already shopping for cat accessories.

The zealous cat adoption ladies helped me fill out our paperwork. They asked me a series of personal questions while Jean was filling her cart.

“Have you ever owned a cat before?” the lady asked.

“Well, yeah, I did have a cat once for four days, but I returned him in like-new condition. We failed to bond on account of his messy habits.”

“Tsk, tsk, tsk,” chided the cat lady. She marked something down on her clipboard, but I couldn’t read it. “You have to understand that having a cat is a commitment.”

Just then, Jean walked up with a cart full of expensive cat products. The cat lady smiled as Jean demonstrated the investment she was willing to make.

“Well,” the cat lady sighed, “I guess you folks are approved.”

“Did you hold it yet?” asked Jean.

“It’s a ‘him,’ not an ‘it,’” scolded the cat lady.

“I’m not ready for that,” I said.

But then I got to hold him the entire way home. He scratched his way out of my grip three times. He grew less cute by the mile.

At home, he was traumatized. So was I.

Bonding would have to wait—we had a wedding to go to that evening. While we were at the ceremony, the cat messed on the carpet.

Over time, the cat displayed a wide range of behavioral problems. Primarily, the so-called “playful” little kitten never missed an opportunity to bite.

He would attack while I watched TV, and he was especially vicious if I fell asleep on the couch. And if I woke up to get a drink at night, I would return to bed with a nasty bite to the ankle.

Nevertheless, sweet Jean gave him hugs and kisses. The cat bit her arms, her cheeks, and her neck.

Not one for pain, I wore oven mitts and boots to protect myself from his “playfulness.”

Eventually, I became so paranoid of the kitten that I searched the Internet for padded dog-training suits at work. The guys in the office thought I was getting a German shepherd or some such animal, which they thought was cool. Eventually, they found out the truth and hurt my feelings.

After a few months, it was time for the cat to get neutered. I was more than a little thrilled—it would be a day of vengeance. After all, how better to get even with the little monster than to cut off his--

The next day, Jean drove the cat to the vet. How she got him in the carrier, I will never know. (She still won’t talk about it, and the carpet is still stained.)

In the absence of the cat, life was good in the apartment. I lay on the floor and watched TV. No biting. No clawing. And the marks on Jean’s cheek, arms, and neck began to heal.

Then I had to pick him up.

The vet seemed to dislike me right away. Each member of the veterinary staff explained how the cat attacked them. In light of all this scratching and biting, I would have expected a better greeting for the guy who would take the little monster home. Oh well.

A nervous assistant brought the cat into the examination room. I held the carrier close to my body, keeping my distance.

“He has some issues with aggression,” the assistant explained.

“Yes, I know, but we love him just the same.” I felt compelled to lie in the presence of this animal lover. “Could you put him in the crate? I’m not really comfortable touching him.”

“Are you allergic?”

“No, he bites.” Gingerly, the assistant stuffed the cat into the crate. I waited for Jean to get home to let him out.

Apparently, the veterinary visit—and the procedure—enraged the precious little lamb, which escalated the violence. He bit, scratched, and pounced. Even Jean wondered if we shouldn’t get rid of him.

“I feel responsible for him--I just can’t take him to the humane society,” she sobbed.

“I’ll do it, if that’s the only problem.”

Jean glared for a moment. “Don’t you dare!”

Monday, April 22, 2013

Short Story: Jim (from 2008 at OU)

“C’mon!” Jim shouts. I wade out of the river,

scurry across the sandy bank, and duck under the chain link fence where he is

holding it up. We look up at the double coil of barbed wire and smile because the US

Fear of the Russians bombing

the bridges and locks keep the base frenzied with activity. Bombers continually

take off and land, flying low and steady over head. Small planes tow winged

targets for fighter jets to blow apart for practice. Large pieces of the

targets’ honeycomb material rain down from the sky over the woods, and we love

to collect the pieces. My dream is to collect enough pieces to create a

complete target of my own.

As usual, no one notices that

Jim and I are slipping under the fence. Jim points at our treasure, and we run

over to the precious trash pile, a heap of scrap metal, old wooden crates, and other junk, which is not far from the banks of the shallow river. Jim scrambles

around the pile, his bare feet precariously close to rusty nails and broken

glass. Water seeps out of my shoes as I climb up a pile of broken pallets. We

work together to free a length of wire from the debris.

Jim stops, stands motionless,

then stoops in the middle of the pile.

“Jack pot!” he calls. Jim holds up a

large .50 caliber bullet. He explains that probably a gun on a tank—or maybe a

helicopter—fires these five-inch-something rounds like that. I rush over to admire

his find, wondering how it got mixed in with the other trash. He hands it to

me, and I rub the mud off the shiny brass casing on my shirt.

“Will you look at that?” I

say, admiring the bullet. “Let’s shoot it off.”

“How you gonna do that?”

“A hammer,” I explain,

holding the bullet upside down and demonstrating a strike with his other hand. “And I’ll

use a vice to hold—”

A green jeep drives around to

corner. It speeds up and heads for the dump.

“They see us! Let’s go!” Jim yells. He grabs the bullet and shoves it in his pocket. We both bolt for the

fence, diving for the opening. We scramble under the fence and splash into the

river. The current works in our favor as we float and swim and run downstream.

No road follows the river, and the overgrowth of the woods prevents anyone from

running along the bank. Still, we move as fast as we can.

When we get out of the river,

we have to decide whether to run down the road or along the Detroit &

Mackinac railroad tracks. We figure they would never guess we took the train

tracks, and so we slowly jog between the rails, stepping from tie to tie.

At a grade crossing, the green

jeeps turns and veers onto the track. We sprint along the roadbed, but they overtake us in an instant. Two

military police guards jump down onto the roadbed with their pistols drawn.

They don’t aim at us.

“Hands above your heads,

boys,” orders one of them. They grab our arms and shove us against

the jeep, forcing my face into the window glass.

“How old are you, son?” the

older MP asks me.

“Twelve, almost thirteen.”

“Well, twelve-almost-thirteen

is too young to die. You boys know you could have been shot as spies?”

“No, sir,” I say.

“You guys can’t even keep

kids off your base,” Jim blurts indignantly.

The younger MP whips Jim

around and presses two fingers against his sternum. “It is against federal law

to trespass on military property like that. Even if you weren’t shot, do you

know what the penalties are?” He pauses, almost challenging Jim to respond. “Do

you?” Jim winces in pain until they spin him around shove him back against the truck.

“What are you boys doing

there?” the older MP asks me.

Thinking about the bullet

makes the blood rush out of my head. “We’re looking for wire.”

“And that’s all?” asks the

other man.

“Yes, sir,” offers Jim.

The older MP looks stern. “I

don’t want to see you on the base again. Ever. We will shoot to kill next

time.” I turn my head around to catch him smile at the younger MP. “You boys

get home.” They let us go, and we run down the tracks.

* * *

A few days later, we meet at the

quarry. It’s almost noon, and Jim pulls the bullet out of his pocket.

“You gonna set it off?” I ask. Jim

looks mischievous.

“You don’t really just want to hit it

with a hammer, do you?” he asks. “How fun is that going to be? We won’t even be

able to hit something with it.”

“What do you want to hit it with?” I

ask.

Jim lists his ideas for

targets: a rock, a tree, a bird, a paper target, glass bottles, and—his

personal favorite— his step-dad’s windshield. “So we need whatever kind of gun

shoots this bullet,” Jim explains.

I think about it for a minute. Sounds

good. “But where are we gonna get a gun?”

“The dump,” says Jim.

“No way, Jim. That’s stupid,” I say.

“Chicken.”

“No, I’m not. You’re stupid. You heard

what they said,” I say. I don’t want any more trouble with the MPs.

“Chicken crap.”

“Gimme the bullet,” I demand. “We’re

not going back to the base.” Jim turns and walks away with the bullet. I shove

him, and he stumbles forward a couple steps. He continues to walk away.

“Chicken,” he says.

“Okay. Fine. We’ll just see if there’s

a gun at the dump, then we’ll leave,” I concede. “But there’s no way they just

threw out a perfectly good gun.”

“Not a whole gun. Just parts. We’ll

put something together.”

We leave the quarry and walk toward

the river. Jim keeps the bullet in his pocket. Jim is almost skipping. His

excitement is contagious, and I forget about getting in trouble and focus on

the bullet. My heart skips a beat as I think about firing the gun. A real gun.

Jim is right—this is going to be great.

At the river, Jim kicks off his shoes,

leaving them near the weeds along the bank and marches into the water. I follow behind him, still wearing my shoes.

We fight against the current, leaning

forward to keep our balance. I can’t get much traction on the slick, green

rocks. The water bubbles and churns around my knees, creating little swirls

behind me. I duck under low-hanging branches, occasionally getting slapped in

the face by twigs that Jim lets fly backward. Finally, the chain link fence at

the base comes into view.

We wade out of the river and approach

the fence. A few iron posts have been jammed into the wet, sandy soil. The

bottom of the fence has been lashed to the post with wire.

Jim tries to pull up one of the posts.

It won’t budge. It makes me nervous that they tried to repair the fence to keep

us out. Now I feel like we shouldn't be here.

“Alright, we tried,” I urge. “Let’s

go.”

“Chicken,” says Jim, working on the

next post. It scrapes its way upward, out of the sandy ground. Jim lifts the

bottom of the fence, and the gap is large enough. Jim does an army crawl,

keeping nearly flat on his stomach, as he moves under the fence. I follow

behind him.

We both take a moment to look around.

It’s quiet, except for the splashing of the river. The coast is clear.

Again, we climb around the trash pile.

Everything seems as we left it. So we get to work. We search and search, making circles around

and through the junk pile. No luck. There are no more bullets and not a single

part of a weapon.

Jim curses loudly. “Let’s

just set it off,” he says, frustrated and disappointed. Jim drags to old cinder

blocks about an inch apart. He takes the round from his pocket and drops it

between the bricks, pointing downward, so that the bottom of the bullet is

flush with the top surface of the blocks. He shimmies the brick closer together

to hold the bullet securely. “Okay, now get me something to hit it with.”

I look around and find a heavy steel

pipe, two inches in diameter and about two feet in length. I bring it over to

Jim, who rips it out of my hands. He is stooping in front of the blocks, his

knees covering his chest.

In a flash, it all feels

wrong. I don’t want to set off the bullet anymore.

“About here,” he says, raising and lowering the

pipe to line up his strike. The pipe strikes the cinder block, missing the bullet.

Nothing.

I wince and back away. He curses as he shifts his weight, preparing for a second attempt.

He raises the pipe again, gritting his teeth. I feel the blood rush out of my face, and my stomach drops. I don’t hear the river. Jim says something, and I don’t really don’t understand his words. I notice his bony shoulder blades slowly sliding under his skin as he raises the pipe above his head. His fingers are wrapped tightly around the pipe, and his knuckles are turning white. He wipes his forehead using the back of his other hand. He grunts and slams the pipe down. An

ear-piercing crack rings out as Jim flops backward.

At first, it's quiet and almost calm as he rolls from side to side. He grasps his leg, crying and groaning. His hands and legs are covered with

blood.

“Jim!” I yell. His left leg is

obviously injured, but I can’t see the wound through the blood. I pull my shirt

off and wrap it around his knee, trying to stop the blood. It isn’t tight

enough, and the wound bleeds in streams. I reposition the shirt and press tightly. Jim screams and screams.

When Jim loses his breath for a moment, I hear the river

splashing behind me. The chain link fence clicks against the metals posts when

the wind blows. Two planes roar by above us.

I hear an engine in the distance,

switching gears and bouncing along. A green jeep turns the curve into the dump.

They drive directly in our direction, stopping in their own dust cloud. The two

MPs leap onto the ground and run toward us. The younger MP grabs his radio and

calls for help. They crowd me out of the way, trying to get a look at Jim’s

injury. I wander toward the fence, but I can’t leave Jim like this.

* * *

Jim was rushed to a big hospital in Detroit

My parents were pretty upset. They

made me work off the trespassing fines and carry Jim’s stuff to and from

school. I would have done that anyway. I wish I wasn’t the one to suggest

shooting off the bullet—knowing full well that Jim would have thought of it, anyway.

When he was feeling better, Jim helped

me reconstruct an airplane target from all the chunks I found in the field. I

tied it together with string and wire, which I purchased at the hardware store.

Jim offered to drag it behind his bike so I could practice shooting at

it. No way.

A Little Background: A coworker once told me about his childhood up north along a little river with a military base not far away. As he explained it, they swam in the river and messed around with shot-up targets and other junk. My uncle told me a story how they hit a bullet with a hammer when he was younger. (Attention Reader: Do NOT do that.) So I wrote this story using a "borrowed" setting and a stupid idea, which I also "borrowed."

A Little Background: A coworker once told me about his childhood up north along a little river with a military base not far away. As he explained it, they swam in the river and messed around with shot-up targets and other junk. My uncle told me a story how they hit a bullet with a hammer when he was younger. (Attention Reader: Do NOT do that.) So I wrote this story using a "borrowed" setting and a stupid idea, which I also "borrowed."

Friday, April 12, 2013

Poem in Progress: Emma Bing

Emma Bing thought she could sing.

Ask her momma and you’ll see why.

“That child can sing!” declares Mrs. Bing,

"So beautifully I could cry!"

So Emma Bing let praises ring

From her pew but not the choir.

“That Emma Bing, her neck I’d wring!”

Said the director before she retired.

Still, Emma Bing sang to her King,

The King of Kings and Lord of Lords.

From Emma Bing, shrill songs took wing!

And became the praises He adored.

Monday, April 8, 2013

Memoire Bit: Healing (from 2008 at OU)

Must be pretty serious. The idea makes me uncomfortable, and I shift my weight in my seat. I don’t really want to know.

My mom and I sit on a bench in a busy hallway outside of the x-ray procedure rooms the hospital. I’m thirteen years old and humiliated in a gown that ties in the back. I look around to be sure that no kids my age are hanging around. Good. Just nurses and old people. Thank God.

An elderly woman emerges from a changing room and sits next to my mom. Her hospital gown is hanging off her ancient shoulders, and I notice the thin, spotted flesh of her chest peaking out. She doesn’t seem to mind and doesn’t bother to pull up her gown. My mom chuckles to herself; I guess she noticed, too.

“A mammogram,” she whispers to my mom.

My mom nods politely and agrees. “Yes,” she says, “we all need to keep up with our regular exams.”

Please just shut up about it. I want to get up and run. I want to run away from this conversation, from my ridiculous hospital gown, from the needles, from my sickness. I don’t know if I can get any more uncomfortable.

The old woman agrees with my mom and goes into detail about this and that. “And here’s the brochure,” she tells me, pointing out the pictures that illustrate her particular procedure. “See? Right there.”

I turn my face away, desperately trying not to see whatever is on the page. Still chuckling to herself, my mom moves the brochure away from me and reassures the old lady. Moments later, a technician calls us into the x-ray room.

“Lots of information, huh?” my mom giggles.

* * *

My mom and dad stand to my left, looking at me with big smiles. I look at them and try to smile back, but my eyelids slide down. I struggle to keep them open. The grey light of a winter afternoon floods in through a window at the foot of the empty bed next to mine, reflecting on the cold tile floor. A stupid animal is painted on the wall.

I realize that a man is standing on the other side of my bed, pulling plastic tubes out of their wrappers.

“No, stop,” I snap in a weak, scratchy voice. It’s all I can speak out.

“Oxygen to help you breathe, just oxygen,” he tells me. I try to protest, but my words come out as mumbles and groans. My parents look at me and touch my face, then reassure the man that oxygen isn’t necessary. I settle down again and relax.

I’m all done! Thank You, Jesus! At last, I feel all the months of pain and illness and fear melt away.

* * *

A nurse enters my room with a syringe, obviously prepared to give me a shot. “Something for the pain, Sweetie,” she tells me.

“No, I’m fine,” I insist. I try to sit up to prove how well I’m doing, but my body doesn’t cooperate.

“No need to be brave about the pain,” she chides.

“No, I’m fine! I don’t want it.”

She is irritated with me. “If you are in pain, then take the medicine.”

“Take the medicine,” urges my mom.

“No, just give me a Tylenol,” I say. “I’m not in pain.” The women frown at me.

My dad intervenes. “If he says he’s comfortable, then just do what he says.”

“Fine. Just wait and see how you feel when you get up,” the nurse threatens. “We’re going to have you out of bed later today.” She practically stomps out of the room.

My mom is upset. She tells my dad that I’m just being stubborn and that I should take the shot for the pain because I am lying here hurting and she can’t bear to see it. My dad tells her I seem fine.

* * *

The first evening after surgery, I receive an all-liquid dinner. Normally, I would be upset, but I have no appetite right now. The aroma of the soup mixes with the odors of the hospital, creating something entirely different smell. I don’t drink my juice or chicken broth, and I leave my square of green Jell-O on the tray. It wiggles when I bump the table.

“Time to get you up,” announces the crabby nurse as she marches into my room. “Need to get you moving.” It’s less than eight hours after surgery, and I’m kind of surprised that she is serious. “Let’s go,” she barks.

My parents timidly clear the tray away and move back the chairs and IV stand. The nurse and my dad come to the side of my bed.

My brain is telling my legs to move, but they feel heavy. I start try to sit up, but it’s uncomfortable. I don’t want to use the muscles under the all the gauze.

When the nurse see me struggle, she slides her hand under my armpit to help me keep my balance. “See?” chides the nurse. “That’s why we want you to have something for the pain.”

Sitting on the edge of the bed, I take a moment to feel my body. I feel the air on my bare legs and my arms and my back, and the blood rushes out of my head, making me a little dizzy. Nothing really hurts. I feel tired and stiff, like standing up after a long car ride. “No,” I say. “I’m okay.”

“Okay, then,” she says.

My dad helps her raise me to my feet. A wonderful revelation washes over me: I made it. It’s over. Thank you, Lord, for taking away my sickness.

Saturday, March 30, 2013

Short Story: The Caboose

Most people seem to remember the low, mournful whistle. Not me. It's all about the smell for me. You see, the railroad works its way into your heart through your nose. It's the aroma of the coal smoke. It's the smell of grease warmed on hot cast-iron skillet. It's the aroma of wood ties baking in the hot sun. And all around, the fresh air bringing the smell of the woods or the factories, depending on where you were. Well, that's how it was back then, anyway.

At first, I thought the caboose smelled like my father. Turns out, my father smelled like that old caboose. I learned that on my first day working for the C&O.

It was the early 40's, and most kids a little older than me were off paying a certain Mr. Adolf Hitler a visit over in Europe . I'd join them in the South Pacific in a year's time, but I was home then, about to start my first real job. My father was a conductor, and he put in a good word for me down at the office. Probably, they would have passed on me until I was a little older, but "beggars can't be choosers," he explained.

So I rode my bike down to the freight yard in the freezing cold, about as nervous as I'd ever been. That day, I would become the newest--and youngest--brakeman on the C&O. Worse yet, my father would be my boss. And I couldn't let him down.

A freight yard is overwhelming to a newbie. Seemed like there were 100 parallel tracks were connected by a thousand switches, and the order of it all was just chaos to me.

Walking past the tower, I could see maybe a half dozen tank cars on one track, at least a dozen coal hoppers on the next track, and a bunch of freight cars that stretched as far as I could see on the track after that. Behind me, the bell on a creeping locomotive clanged, warning lost souls like me to keep out of its way. My ears burned in the cold.

"Tommy!" called the yardmaster. I looked up at him in the tower.

"Good morning, Mr, Johnston

"Better get yourself into that cabin car, or your old man's gonna tan your hide!" he hollered with a smile. "Track 5, Track 5! Oh, and see me to sign your papers when you get back--no time now! Welcome aboard, son!"

I waved and trotted along the freight cars standing coupled on track five. The red caboose was in sight, maybe twenty cars down. My father waved from the front platform.

At the caboose, my father handed me a pair of large leather gloves and checked his pocket watch as we went inside. There was that wonderful smell inside--grease and solvent and coffee and then just coffee as the pot came to a boil on the stove.

"I don't need to tell you that we keep a tight schedule," my father chided with a wink. "It's your first day, so I'll let it slide."

He stepped out onto the platform again, leaning off the side and signaling the locomotive with his hand. "We got Joe and Sam up front, so this will be an easy run." Joe and Sam were the engineer and fireman, an experienced crew, and more of my father's buddies. Joe answered my father with two whoops from the whistle.

"Brace yourself now," my father warned me as he handed me a cup of coffee, "Joe means business." As the locomotive moved forward, gaining speed, the slack went out between the cars, jarring each one until the jolt caused me to spill half my cup. My father skillfully took a swig at the right moment, and he didn't spill a drop.

"Well, good thing this isn't your mother's parlor." He winked again. "But let's keep this place clean." He tossed me a dirty towel, and I wiped the floor.

Now that we were underway, my father got down to work. He organized his paperwork--freight waybills, crew time sheets, train orders, explaining each document to me. Sure, I was a brakeman, but he was training me to be a conductor one day. And as the train entered a curve, he just about lifted me off the bench I was sitting on and dragged me over to the window for a spectacular view of the train. Sam waved at us from the locomotive's cab. We were now approaching our first stop.

"OK, here we go," my father said, buttoning his jacket and putting his work gloves back on. "Watch carefully. This is big equipment, and we need to make sure that we're safe. And this is a get-it-right-the-first-time kinda job."

He went to the platform and signaled to Joe to stop the train. We walked back a ways and dropped a signal to let approaching trains know that we were blocking the line, and then we walked up about 25 cars.

"We cut in here," my father explained, slamming the coupler open. He signaled to Joe, who answered back with two whistle blasts and pulled forward, breaking the consist in two. Once they passed a switch, they stopped the train.

My father demonstrated how to operate the lever and rotate the switch, preparing for the locomotive to back onto the siding to collect more cars. Then we walked down the siding where we were to collect three empty boxcars. My father stopped dead in his tracks when we were just about up to the first car. He flung one of his big arms out to block me, and I stopped in my tracks, looking over at him. I could tell he was concerned.

"We got company, I'd say," he whispered. I heard a loud cough echo from inside the boxcar. And then an unhealthy hacking cough, followed by a moan. "Hang back here, son. You never know with these guys..."

Now, I always knew that folks hopped aboard freight trains to catch a free ride. The stock market crashed over ten years earlier, and men took to the rails in droves, riding around until they found work. Or maybe just riding around because they had no other life to get back to. Problem was, there was always lots of booze, and where there's booze, there's trouble. When I was little, my father was roughed up by a few guys when he kicked them off the train. I was old enough to remember.

My father walked ahead of me. "All right!" he bellowed. "Out of the car! This is the end of the line for you." Everything was absolutely silent for a few long seconds until another raspy cough rang out.

The boxcar door slid open another foot or so, and an old man hopped down from the car. He wore a dirty jacket and carried a filthy bag. His right pant leg was torn at the knee, and his stubbly beard was mostly white. He was hunched forward a bit; he rubbed his crooked back after jumping down. Now he looked at us with a blank, defeated stare. He coughed again, and I could see his breath in the cold.

"Well, we can't have this," my father said. The old man looked down. "Where you headed, old timer?"

"Back to the city," the old man said, his eyes still fixed on the roadbed. He was waiting for my father to tell him to get off the railroad's property. That was the rule; in fact, he could be arrested for trespassing. And some railroad bulls would be more than happy to remove him toss him over a fence, just to get the idea across.

"The city, huh?" My father sighed. "Well, not in a boxcar. We can't have that. I won't tolerate it." He turns to me and winks. "No, I won't tolerate it for a moment. So you'll ride in the cabin car with us."

When I heard this, I was furious. Now, I'm not sure why, but it was as if I snapped. Was he serious? Didn't he know this was against regulations? Why would my father risk getting himself into trouble--and me--for some old stowaway? I didn’t want the superintendet coming down on him for this lapse of judgement.

"Father, you can't let him on the train!" I blurted. "Don't be wreckless! Even I know that'll cost us our jobs!" My ears were stinging again, and my hands were starting to ache. But my cheeks were warm with anger.

"I've got a lot to teach you still, don't I?" my father gently scolded, shaking his head. "We will be just fine," he assured me. I stood staring at the old man, and he looked at me, desperate and cold. "Well, both of you, come on," barked my father. "We have a schedule to keep and we're losing time. I am the conductor here. This is my train. And I won't be late."

We walked back to the mainline, where my father signaled Joe again with his hand. As Joe started to back down the siding, my father sent me to the back of the train to collect the signal. And to calm down. By the time I was back to the caboose, the locomotive had pulled the three empties off the siding, my father had thrown the switch, and Joe was slamming the train back together.

Without talking, I climbed the steps to the caboose with my father and his new passenger. The cabin was very warm. Again, my father signaled Joe, and off we went with a series of slams. Bang, bang, bang, as the slack was let out.

My father poured coffee into our tin mugs and got a third down from a shelf. He blew the dust out of it, then poured a cup for our passenger. Shortly, we made another stop to cut in two gondolas. The old man waited inside while we worked. Once we started out again, there was time to talk.

"We got another 12 cars to collect and 18 cars to drop off before we get back to the yard in the city," my father told us. "This is an easy trip with Joe and Sam up front." The old man nodded in polite agreement, but it didn't feel easy to me. "Say, what brings you to the city?"

"Going home," said the old man. "It's been over ten years since I been back." He coughed again.

"Ten years? That's a long time to be away."

"Well, I didn't plan on coming back."

"No?"

"No, I was looking to work in the South where the weather isn't so bad as this," the old man explained.

"I can imagine a little sunshine would do the body a world of good," agreed my father.

"Yes, that's right," the old man smiled. He rubbed his back for a moment. "It's harder to work outside at my age, but I was going to get by."

"So back to the city in the winter?"

The old man teared up a little. "I received word that my brother is taken ill, very ill," he choked out. "That was two weeks ago yesterday, and I hope he's still with us."

I felt burning ashamed. I was so selfish to try to throw this old man out into the cold. I fought back the tears that came from shame and from hearing this story.

Just then, Joe's whistle warned us of the next stop. And then the stop after that and after that. We got about two miles from the yard when my father reached for his wallet.

"Here's six dollars," he said, placing it in the old man's hands. "It's all I have, but it should be about enough for bus fare and dinner. When we stop the train the throw the switch at the yard, I'm going to ask you to get off and walk down the embankment. When you reach the street, make a right and keep going until you get to a diner. You can eat there and catch the bus around the corner."

I pulled two quarters from my pocket and gave them to the man, too. "I hope your brother is OK," I told him.

As Joe slowed the train, the old man thanked us and then hopped down from the last step on the platform. Despite the crooked back, the old man exited so gracefully that I could tell he had done it a thousand times before.

I stepped onto the back platform and waved as we continued forward through the switch into the yard. The old man waved back and then turned to press through the dry weeds.

I was so proud of my father that cold night. I can't hear a horn or a whistle or the clanging bell at a grade crossing without thinking of my father's kindness. Or the smell of coffee in that caboose.

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

Short Story: The Brother (from 2008 at OU)

That snowy night, Mother screamed out. I think she had been expecting it; I remember how she winced and paced and worried the day before. It was twenty past one in the morning on February 21, 1887. The thin layers of plaster, lathe, paper, and paint couldn’t keep out the sounds and commotion. How I do remember that scream!

Father was still driving a wagon train back from St. Louis

When Grandmother first arrived at our house for this visit, it was a week before Mother’s labor started. I heard Mother tell her that this time would be different. “The Lord doesn’t want to take this one,” she explained. “I feel it in my heart.” Mother looked at me with a crazy smile.

After all the deaths, I did not think that this new baby would live for very long. I smiled back nervously because the losses were clouding her mind. Looking back, I would call it hysteria of some sort.

Grandmother wasn’t smiling. “The Lord does not want any babies, Elizabeth,” she said. “Babies live full lives when they are born to a strong mother.” Mother sobbed at the insult and retreated to her room, where she stayed for several days.

Now I listened to Mother groaning and panting and pleading. I began to worry that Grandmother didn’t hear these horrible cries. Grandmother always helped Mother when it was time for the babies to come, just like she helped Aunt Rebecca. My three sisters didn’t make it more than an hour after their births, but Aunt Rebecca never lost a baby.

I slid out of the warmth of my bed, and my feet touched the cold, bare floorboards. I was standing next to the low window in my bedroom. The cold flowed through the thin, slightly rippled panes of glass, and, to add to my discomfort, the window sash never seated properly on the twisted sill, leaving a sizable gap. I felt the freezing wind on my knees, and quickly tiptoed away from the window. I crept to the door, turned the round metal knob, and pushed the door open. The door creaked loudly.

I saw that Grandmother was climbing the narrow staircase at the end of the hall. The flickering light from Mother’s lamp poured out into the small landing area. Grandmother was already wearing her blue dress and an old, stained apron. In one hand, she carried a steaming kettle, and her other arm was wrapped around a stack of towels. I was relieved to see her stern, pale face. She was like an old priestess, preparing to conduct a familiar ritual. Mother still trusted her skills as a midwife, still unfamiliar with the impersonal, sterile treatment of a modern physician.

“Is the baby going to be alright?” I asked. I knew it was not my place to ask such a thing.

She stared at me coldly. “The baby needs your mother to work hard.”

Mother needed to work hard, I thought, Grandmother’s words echoing in my mind. Mother needs to work hard. Work hard? I considered the notion that my Mother had to work to make the baby become born. And for the first time, it occurred to me that I did not know how the babies came out. I wanted to ask, but it was difficult to get the words out.

“How does the baby—”

“Not appropriate, young man,” she said. “Let’s not be obscene with a brand new baby almost in earshot.” Mother screamed and panted rapidly. Grandmother pushed her way around me and slipped into my parent’s bedroom. She shut the door behind her, and the house was entirely dark. Standing alone in the small upstairs landing, I sensed something awkward, something dirty. I was embarrassed. Perhaps Grandmother saved me from something horrible, I thought.

Mother screamed again, and I heard Grandmother saying, “Hush now. Hush.” It felt wrong that Mother wasn’t allowed to scream if she needed to. If Mother was working hard, I wanted to help her.

I thought about Mother. I remembered how she would warm milk on the stove for me when I was younger. I remembered the time I had a raging fever, and she lie next to me in bed for the entire night. So many memories flooded my mind. Mother’s cries and screams began to tear my heart. I just wanted to help her, but Grandmother would never allow it. It was not my place.

All I could do was to try to escape the sounds of Mother’s hard work. I wandered downstairs, sliding my hand down the railing. The paint was worn off, and the wood was literally polished from contact with human hands over the decades. I sat on the bottom step, staring at the front door. The snow whipped against the windows. It was too cold to wait outside, like Father and I did last time. We sat on the porch, and Father was happy and proud. It was the best evening I ever had, until we went back inside. Father held the limp, bluish body so gently that I thought that the baby might be alive. Mother and Father were sad for months and months.

Grandmother yelled from upstairs.

I bolted to the top of the narrow staircase, stopping just outside of Mother’s bedroom. Grandmother was standing in the doorway, and I could see Mother lying in bed. The sheets were bloody, and blood was smeared up her bare legs, which I had never seen before. Blood-soaked towels were wadded in a bedpan. Grandmother’s hands were bloody past her wrists, and she was mopping them dry with another towel. “A foot. One foot. The baby can’t come like that,” Grandmother stammered. “I tried to turn the baby, but there is no room.” She threw the towel onto the small woven rug at the top of the stairs. “I was afraid of this,” she said.

Burning tears welled up in my eyes. “What are you going to do?” I pleaded.

“Fetch the doctor immediately,” She looked at me, and I sensed her urgency. “You know where Dr. Jackson lives. Run there right now and tell him that the baby and your mother are in trouble. And I pray your father returns home.” She turned quickly, closing the door as she entered the room.

I dashed down the hall and pulled on my pants and a sweater. Downstairs, I shoved my feet into my heavy boots, and pulled on Father’s huge wool coat. Upstairs, Mother was groaning.

I opened the door and rushed out into the beautiful, bright silence of a heavy snowfall. A wonderful numbness set in almost immediately; it was too cold to feel the sharp sting of the wind. The white slopes and hills reflected a soft light, and the never-ending frosty blanket deadened the sound.

My heart raced. I slammed the door and hurried down the porch steps. As I ran for the front gate, my legs sunk up to my knees with each step. Crunch, crunch, crunch. Despite my best effort, my pace slowed with each heavy step. It took a great deal of effort to reach the gate, where snow was piled in a high drift. I scrambled over a miniature mountain of snow, touching the crest with my bare hands.

I hurried down the street, walking in carriage tracks wherever possible. My legs felt heavy and cold, but I hurried as fast as I could, laboring through the snow with little progress. The cold air burned my throat, and my bare hands throbbed in the wind. Through all of this, Mother’s screams echoed through my head, and images of her bloody legs flashed in my mind. I sensed that both Mother and the baby were in peril.

At last, Dr. Jackson’s house was in sight. I climbed the steps to the porch, hoping that Dr. Jackson has already seen me approaching. I peered through the sidelights at the front door. The house was dark.

“Dr. Jackson?” I called quietly. No answer. No answer. Mother was bleeding at home, and no one answered. “Dr. Jackson!” I called. Still no answer. I pounded on the door with both fists. As if I were dreaming, I could see a light appear at the top of the stairs. Dr. Jackson was coming down, tying his robe around his waist.

He opened the door. “What is it? Who’s there?”

“It’s me,” I said, “John Montgomery.”

“What is it, son?”

“My mother,” I panted, “The baby. One foot.”

Dr. Jackson turned for the staircase. “Come in, John. I’m going to help her.”

I stood near the door, and the doctor was dressed and back downstairs within moments. He grabbed his black leather bag from the parlor and beckoned me to follow him. He ran down from his porch and across his snow-covered lawn. His long legs carried him over the deep snow bank near the walkway. I chased him down the street, but he didn’t wait for me. I couldn’t keep up. The doctor ran ahead and out of sight. Mother needed him.

I bent over and placed my hands on my knees to catch my breath. Again, it was quiet and cold. All at once, the painful cold burned my ears, my hands, my nose, and my feet. It felt like the wind blew through my coat. I hoped that the doctor was already at my house. Stiffened by the cold, I walked slowly toward home.

When I opened the front door, I heard Dr. Jackson upstairs. Mother was still panting, and her screams were sounding tired.

Grandmother paced to and fro in the parlor, just like Father did. Her apron was bloody. She came to me. “Thank you, John,” she said. “The baby just wouldn’t cooperate. You helped me do all we could. Now it’s the doctor’s turn.”

I lowered my head, quietly praying that this time would be different. That they wouldn’t have to return to the darkness of grief and mourning. That Mother and Father would have a reason to celebrate.

And I knew God would hear me.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)